New York Center for Facial Plastic Surgery

Schedule a consultation

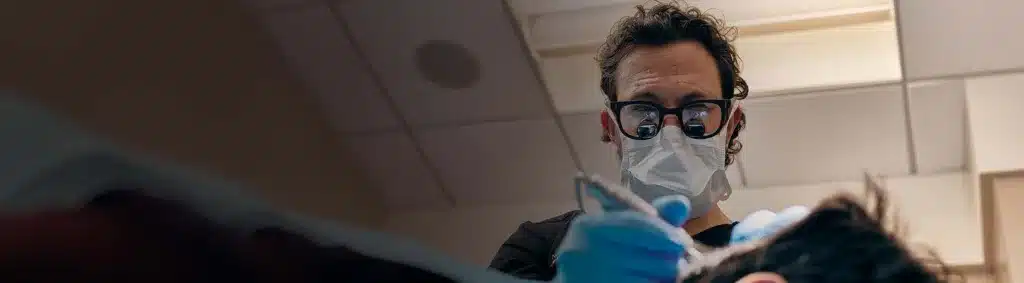

New York Plastic Surgeon, Dr. Andrew Jacono, Discusses Facial Skin Cancer Treatments

Dr. Jacono is a specialist not only in cosmetic surgical procedures but in preventative and reconstructive treatment. He regularly treats patients who have melanomas of the skin.

Melanoma is a form of cancer that begins in melanocytes. These cells produce the pigment melanin. Usually, melanoma begins in a mole on the skin, but can also form in other places, like the eyes or intestines.

Darker-skinned people can and do get melanomas. Unfortunately, these people also have higher rates of death due to the disease. This is because their cases are usually detected and treated later. “I routinely treat patients with melanoma,” says Dr. Jacono. “The course of action is to perform surgery to excise the affected tissues. It makes me quite happy to see how people’s lives change thanks to such a simple surgery.”

Melanoma can affect anyone of any age, though older people are certainly at a higher risk. This is why it is especially important to have routine checkups.

David Estrada and his mother, El Salvador natives who moved to Long Island, were in a car accident. Both suffered injuries. David’s were far less serious than his mother’s, though after an examination, doctors determined that he had a large, precancerous lesion on his scalp. He was 16 years old.

Prior to the Estrada family’s arrival in the United States, David’s mother and doctors knew about the growth but felt it wasn’t a threat. They didn’t realize that it could eventually become basal-cell cancer and threaten David’s life.

To fix the problem, David underwent surgery. Dr. Jacono performed the procedure at his Great Neck location. He treated David with the help of Beyond Our Borders, a small nonprofit group. The organization provides free medical services and humanitarian relief in El Salvador and other countries.

“The operation required 20 injections of local anesthesia,” says Dr. Jacono. “The lesion was thick, had a large circumference, and had roots. It had eroded into the underlying tissue and needed to be removed in layers. I placed 60 stitches to close the wound. It was rather complicated, but it is much easier to treat lesions in their early phases. The great thing is that David is cured and doesn’t have to worry about this turning into something more serious.”

Estrada’s case is unfortunately very familiar to researchers, dermatologists, and surgeons. Studies from the American Academy of Dermatology assert that melanomas are likelier to go undetected in darker-skinned individuals. In many cases, they advance to a later stage before they are properly treated.

So, while African Americans, Hispanics, Indians, Middle Easterners, and others have fewer incidences of skin cancer, they tend to have a higher death rate. Figures from the Academy show, for example, that the 5-year survival rate for white people with melanomas is 85 percent. On the other hand, African Americans have a 59-percent survival rate over 5 years.

Furthermore, Dr. Susan C. Taylor, a dermatologist, cited a study that found that later stages of skin cancers occur “in almost three times the number of blacks as opposed to whites.” She also noted that there is a popular misconception among those with darker skin that they have enough natural protection against cancers. As a result, these individuals don’t perform frequent self-exams. They also aren’t taught the warning signs of skin cancer. Worse, most skin cancer warnings are directed toward those with fairer skin, blue eyes, and blond hair.

“One of the biggest issues we face is that there are plenty of free skin cancer screening clinics, and few darker-skinned people attend,” says Dr. Jacono. “Our mission should be to educate people about the fact that skin cancer does occur in people with darker skin, even with a lower rate of incidence.”

Until there are advances in skin cancer education, the reality remains that the vast majority of patients of color believe the pigment in their skin is enough to ward off disease. Only a small percentage of this population is aware that protective caps and clothing are a must, as is sunblock. While sunblock can leave behind a chalky film on the skin, manufacturers have started selling sunscreen products that circumvent this issue.

People should also make sure to protect their skin year-round, and not just during warmer months. Even though winter brings snow and cooler temperatures, the sun still emits UV rays that instigate skin damage. In some areas, solar rays can be even stronger than normal.

New York Center for Facial Plastic Surgery

Schedule a consultation

As effective and accessible as medicine has become in recent years, there are still problems to be solved. Many primary care physicians, for example, tend to minimize the need to examine dark-skinned patients for skin cancer.

“The truth is that primary care physicians are constantly overloaded,” says Dr. Jacono. “Their volume has increased, and skin cancer or skin problems are sidelined. Doctors tend to worry about everything else first.”

If nothing else, these facts are a testament to the need for better patient-physician communication. Doctors should try their best to evaluate their clients holistically and as free of judgment as possible. Patients, too, should be willing to listen to their doctors’ advice.

Accessibility: If you are vision-impaired or have some other impairment covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act or a similar law, and you wish to discuss potential accommodations related to using this website, please contact our Accessibility Manager at (212) 570-2500 .